back to all news

back to all news

Black History Month Honors Professor Emeritus Bunyan Bryant

As we commemorate Black History Month this February, we celebrate Black stories, achievements, and reflect on Black history.

Professor Emeritus Bunyan Bryant is recognized as a leader in Environmental Justice, and over his 40-year career was instrumental in establishing the school’s Environmental Justice program, focusing on the differential impact of environmental contaminants and climate change on people of color and low-income communities.

In 1972, Bunyan Bryant became the first African American to join the faculty. In 1990, he was co-principal investigator of the U-M Detroit Area Study on Race and Toxic Waste. Along with faculty member Dr. Paul Mohai, Dr. Bryant organized the Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards Conference held at the School of Natural Resources (now SEAS) that same year. The historic conference would help to springboard environmental justice as an academic discipline. SEAS celebrated the 30th anniversary of the historic EJ conference in 2020 with national and regional leaders in the EJ movement. The SEAS community was very appreciative that Dr. Bryant was able to attend.

Earlier on, Dr. Bryant's advocacy efforts were recognized by Flint, Michigan in 2008 with a Lifetime Leadership Award. He also received the 2017 Environmental Justice Champion Award at the Flint Environmental Justice Summit in 2017.

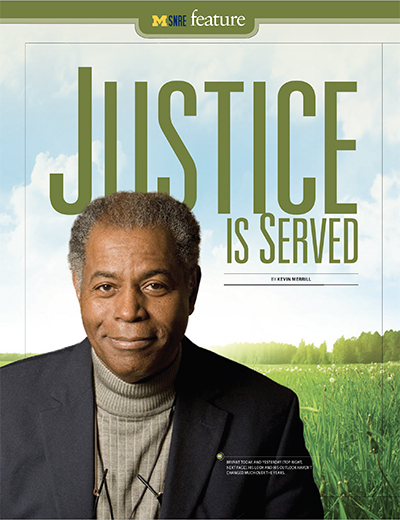

In 2012, as Dr. Bryant was nearing retirement, the school organized the conference, "The Legacy and Future of Environmental Justice: Honoring the Career of Bunyan Bryant." In that same year, the fall issue of Stewards featured the story, "Justice is Served," providing insight into Dr. Bryant's remarkable life and career. The 2012 story appears below in its entirety.

Justice is Served

As an 8-year-old growing up in his hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas, Bunyan Bryant was taught by his mother to be proud of his heritage and how to survive in the segregated South. Teaching him the social conventions of the time, she advised him that when dealing with white people, step out of the way when sharing a sidewalk, avoid eye contact, use “Sir” and “Ma’am”, and always move to the back of the bus.

Professor Bryant, now 77 and nearing retirement, has for decades taught students to challenge those social conventions in their multiple forms, by instead stepping confidently into the fray, not looking away, making yourself heard, and finding a seat wherever you can, whether at the table or on the bus.

Challenging social conventions has become Bryant’s calling card, whether receiving a disorderly conduct citation for trying to get a haircut in a barbershop that only served whites, or submitting a list of hiring demands that he dared his prospective employer, the School of Natural Resources, to meet. Bryant hopes a new generation is ready to pick up where he is leaving off after helping to define the field of Environmental Justice and serving four decades as a researcher and mentor.

“Things have changed, but for me, they haven’t changed enough,” Bryant said, reflecting upon his upcoming departure from the University of Michigan.

To honor him and promote the change he has long sought, the School of Natural Resources and Environment is organizing an academic conference Oct. 4-6 in his honor. While the event includes a Friday tribute dinner, its focus is on bringing activists and academics together to create a roadmap for the movement. Organizers hope the October conference has an impact as lasting as a 1990 conference Bryant organized with SNRE colleague Paul Mohai.

In 1958, after graduating from Eastern Michigan University with a bachelor’s degree, Bryant spent a year in Bethesda, Md., working for the National Institute for Mental Health on a special project involving the treatment of five mentally disturbed boys. Before and after his later graduation from the U-M School of Social Work, he was a youth counselor, social worker and program director at several Michigan-based agencies.

As he completed his doctorate in educational psychology at Michigan, he was part of a generation of student activists who helped to alter and reshape the nation’s consciousness. He was part of the civil rights and peace movements, and witnessed the women’s, countercultural and environmental movements that shattered time-honored conventions both on campus and across the country. In 1970, the ecology teach-in and the Black Action Movement takeover of campus showed such actions were necessary to gain the attention of decision-makers, so student pain and grievances could be felt and heard. “What these movements had in common is they were all anti-establishment,” Byrant said. “This was a tumultuous time.”

In a sense, those events set the stage for him to become an SNRE faculty member.

SNRE seemed an unusual place to welcome Bryant and the type of social advocacy that would help define the Environmental Justice field. SNRE Professor William Stapp established the school’s international reputation in environmental education—a program which had its intellectual roots in the school’s historic role and leadership in conservation studies. The leap to environmental advocacy was looked upon warily, or so it seemed to Bryant, who received a call while working at U-M’s Institute for Social Research. The school, looking to integrate the environmental enthusiasm spreading on campus and across the country, was interested in using the environment as the focal point for organizing. It wanted him to teach students the community organizing techniques he learned as a social work student and community organizer in the civil rights movement.

“I said, ‘you’ve got the wrong guy. I don’t have any background in natural resources,’” Bryant recalled.

But the wooing continued, and he eventually made two presentations to faculty and students as a part of the hiring and interview process. When the offer came from SNRE Dean James McFadden, Bryant submitted a list of hiring-related requests. Included was a special $10,000 fund—$55,000 in today’s dollars—to finance placing students in the field to practice advocacy. “I packed in as many ideas as I could,” Bryant recalled of the list. A month went by, and then the school called. They said yes to everything, but countered on the student funding request with $5,000. Bryant said yes, and joined as an assistant professor in the fall of 1972, along with Jim Crowfoot, where the two built the environmental advocacy program.

In the decades that followed, he would write books, win awards, serve on national boards and councils and advise doctoral and master’s students. He also found time to found the Environmental Justice Initiative (EJI), a research and outreach center; organize Environmental Justice Poetry Slams; establish the Environmental Justice Theatre Troupe; organize retrieval and dissemination conferences; and along with colleague Elaine Hockman, EJI’s research director, create a database from which to publish books and articles.

He would still be teaching and mentoring today, he says, if not for the worsening effects of Parkinson’s disease. Diagnosed in 2002, he has learned to live with the tremors and other side effects, but the battle is never-ending. It has prematurely brought on his retirement, which becomes official in December. “It’s a monster. I’d like to have taught a few more years. I’d like to have taught another five years. My heart is there, but physically, I’m not,” he said.

He looked very determined and steady in April, when he was selected to give the 2012 Commencement address to graduating SNRE students at Rackham Auditorium. Mixing verse and rhyme with his trademark optimism, he inspired and humored the 600-plus guests.

He looked very determined and steady in April, when he was selected to give the 2012 Commencement address to graduating SNRE students at Rackham Auditorium. Mixing verse and rhyme with his trademark optimism, he inspired and humored the 600-plus guests.

But his contributions to SNRE and Environmental Justice may not have happened if he first had not met Jean Carlberg.

“I was race conscious at a very early age,” Bryant said. “I knew blacks lived in inferior neighborhoods, in inferior housing, and their education system wasn’t as good as those available to whites. That was the nature of the beast. That was the norm. I didn’t challenge those norms until I started at U-M and until I met Jean.”

They met at a Michigan Fresh Air Camp staff party, where Bryant had been a counselor. For 50 years they have been at the forefront of activism in Ann Arbor. Only Carlberg, however, has spent a night in jail, in the early 1960s, for protesting in favor of the city adopting a fair housing ordinance. In 1994, that same Jean Carlberg was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council and would serve for 12 years.

Whatever the source of the initial attraction, she had another purpose for furthering the relationship. As a member of the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, Carlberg supported Bryant in pursuing a test case to demonstrate that despite a fair housing ordinance on the books, racial discrimination was rampant in Ann Arbor. Bryant had been denied an apartment in Ann Arbor, and together they organized a response, using the resources of CORE.

The organization sent two white students to inquire separately about apartment rentals at a particular building. Each was told a vacancy existed. Bryant went in alone after and before the other students, and was told no vacancies existed. The Congress of Racial Equality later discovered that the University of Michigan held the mortgage on the building, but was using a private, separate business to manage it.

“As a student, I was paying tuition. As a student employee, I was paying taxes to the state, which helped subsidize the university,” Bryant said. “It was almost as if I was paying for my own discrimination. That mobilized me. To this day, I still have some ambivalent feeling toward the university over the issue.”

Bryant’s housing discrimination case helped to provide the initiative for the state Supreme Court to determine if the city’s fair housing ordinance could co-exist with housing as a civil right as embodied in the state constitution. The court supported the legitimacy of Ann Arbor’s ordinance because it did not conflict with the new state constitution. Because of a legal technicality, Bryant was never able to rent the apartment.

Despite that verdict, Bryant has had a long and fruitful relationship with SNRE. To support its students, he and Carlberg in 2007 established the Bunyan Bryant Scholarship Fund in Environmental Justice. “When I came to the University of Michigan, I was used to looking at the world through a certain frame. That frame was civil rights,” he said. “When I got to SNRE, it offered me another frame, and that was the environment. The two morphed for me.”

“The simple definition of Environmental Justice has always been ‘Close down the incinerator’ or ‘Close down the landfill’ or ‘Close the sewage treatment plant’—basically, reacting to someone else’s agenda,” Bryant said. “It has to be more than that. We must become more proactive and that’s harder to do. We must become visionaries and take the battle to the next steps.”

The next steps, he says, are to act on his definition of Environment Justice, even though what he describes sounds like a community of the future.

“If we aspire to make real Environmental Justice, we need to have hope,” he said. “Hope gives meaning and direction to our visions and actions; it reaffirms our existence and gives us confidence in what we can become and the kind of communities we can build for ourselves and for our children. Hope is important because without it, we are lost.”