back to all news

back to all news

Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan: Place Where Medicines Grow Well

Recent SEAS graduate Eva Roos (MS/MLA ’21) collaborated with the Cheboiganing Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians for her master’s practicum, “Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan // Place Where Medicines Grow Well.” Current-day Emmet and Cheboygan counties include the traditional home territory of the Burt Lake Band, also known by their historical Anishinaabeg name as the Cheboiganing Band. Roos credits the inspiration for this collaboration to her time spent as a teaching assistant for the U-M Biological Station (UMBS) humanities program, Great Lakes Arts, Cultures, and Environments (GLACE), directed by Ingrid Diran.

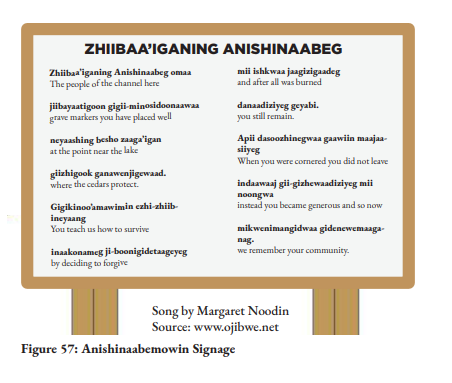

At GLACE, Roos worked with visiting professor Margaret Noodin, an Anishinaabemowin language holder, poet, and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Diran and Noodin helped brainstorm ways in which Roos’ master’s practicum interests could be met: to bring Indigenous culture, aesthetics, and history into the field of landscape architecture. Noodin bridged a connection between Roos and the Burt Lake Band. In December 2019, Roos submitted a proposal, presented on her behalf by Burt Lake Band historian, Richard Wiles, at a tribal council meeting. Wiles shared her open-ended offer to provide her landscape architecture skills to address any design needs of the Band’s new headquarters in whichever ways desired.

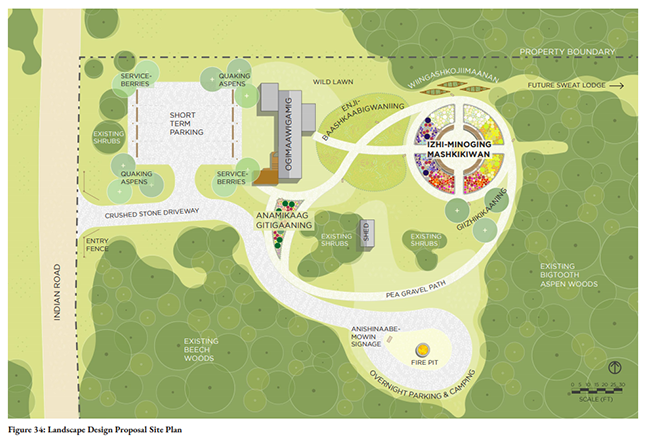

In recent years, the Band had placed an office on their 20-acre headquarters in Brutus, Michigan, and were still deciding how to better relate the landscape to the building and their needs. Roos discussed ideas with Burt Lake Band Tribal Council members, who were mourning the loss of Isabel Scollon, the previous executive director of the Burt Lake Band. Scollon envisioned this central gathering spot to be a “place of healing” for her people. Together, tribal council members of the Burt Lake Band and Roos proposed a garden that would integrate the native plant knowledge, cultural beliefs and motifs, and traditional practices of the Anishinaabeg, a group of culturally related indigenous people who span a variety of regions including Michigan, Minnesota, and Ontario.

The final healing garden was named in Anishinaabemowin as “Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan” or, translated to English by Noodin, “Place Where Medicines Grow Well.” The medicine garden is the main feature of the project, but Roos also worked on the Anamikaag Gitigaaning // Welcoming Garden, Wiingashkojimaanan // Sweetgrass Canoes, Giizhikikaaning // Cedar Grove, Enji-Baashkaabiigwaning // Flowering Meadow, and a short- and long-term parking/overnight camping site. The garden was a partnership, with Roos deferring to the Band for input and guidance for each iteration to ensure that careful cultural integration and collaboration took place throughout every aspect of designing the garden. Roos was advised by Dr. David Mitchner, curator of U-M’s Botanical Gardens and Arboretum, and Nola Parkey, executive director of the Burt Lake Band.

History of the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

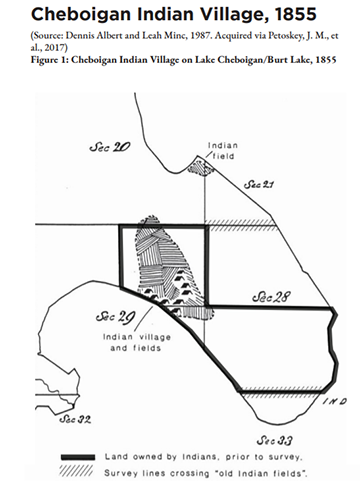

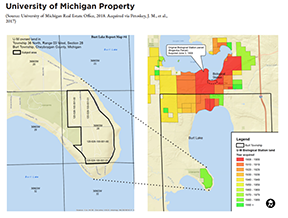

To properly contextualize the Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan project, the history of the Cheboiganing Burt Lake Band should be acknowledged. Chief Chingassimo of the Cheboigan Indian Village, as the Burt Lake Band community was known at the time, signed the 1836 Treaty of Washington. The treaty stipulated that in giving up 13.6 million acres of the Anishinaabe Nation’s land, the Nation would receive farming equipment, education, erasure of debts, and preservation of ancestral land for every Band who signed the treaty. The treaty gave 1,000 acres of land at “Indian Point” on Lake Cheboigan to the Burt Lake Band around Burt Lake. Roos notes in her practicum that “on October 15, 1900, Fred Ming, a white Cheboygan county sheriff, and John McGinn, a white timber speculator, illegally evicted residents of Cheboigan Indian Village and burned each home to the ground.” The altered name of the place itself represents the crime. Originally referred to as “Cheboiganing” an Algonquin word meaning “a place of passage,” the region was then renamed Cheboygan by white settlers who also renamed the lake to Burt Lake after “William Austin Burt who measured the land in the mid-1800s."

This destruction forced the Burt Lake Band off their ancestral and legally promised land and forced them to flee on foot to the Burt Lake area. The Band’s land was later sold to white settlers and logging barons for profit. In 1909, the University of Michigan would acquire this land from loggers in order to establish the UMBS. In 2018, U-M President Mark Schlissel established a committee to “investigate the burnout and make recommendations for actions that would acknowledge this history and incorporate lessons learned from this event into our education, research, and outreach missions.” U-M now strives to incorporate the natural and cultural histories of the Burt Lake Band’s historic land with all activities and research that take place on-site at the UMBS. It should be noted that current members of the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians are currently seeking federal reaffirmation of their tribe’s legal status in order to revalidate previous treaties signed with the federal government. This previous treaty was signed by the Band and the federal government in 1836, yet the conditions within have not been legally recognized or enforced since 1900. This reaffirmation of their federally recognized status would allow them certain rights of self-governance, access to federal benefits, legal protections, and even a chance to reclaim the land that was stolen from them over 100 years ago.

Roos’ practicum in collaboration with the Burt Lake Band is an important example of creating reciprocal relationships with marginalized communities that have been disenfranchised by systemic discrimination and racism. Roos said she did not approach the project as a way to elevate herself, but as a way to put her ecological landscape architecture skills to use in a way that the community desired. “It’s so important that the underlying design concepts come from members of the Band. To me, a successful design creates an experience where members of the Band see themselves in this landscape, and they can continually rediscover that identity and their culture and learn from this place together as a community,” said Roos. The idea of a space of healing became a driving force for the entire Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan garden.

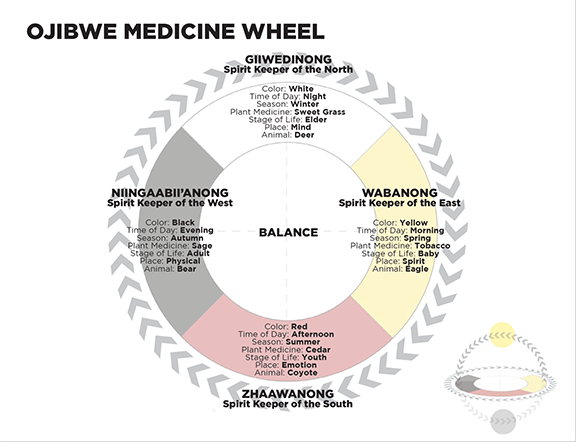

The Ojibwe Medicine Wheel

In many Native American cultures, a concept known as the Medicine Wheel is used as a sacred teaching symbol. Variations of this wheel and the lessons it holds change by region, but within the Anishinaabe traditions, it is represented as a circle with four even sections. Each section represents a different compass direction and color, and is associated with other symbology. The four sections represent the following (Roos, p. 17):

- Waabanong//East: Where we come from, begin our journey

- Zhaawanong//South: The time of growth and youth

- Niingaabi’anong//West: Reminder of constant change within us, the death of former selves

- Giiwedinong//North: Period of rest, contemplation, wisdom.

More information about the Medicine Wheel as used by the Anishinaabe can be found on the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community's Health facility website. These teachings vary from tribe to tribe, and this resource is specific to the Anishnaabe people of the Lake Superior Band of Chippewa Indians, Ojibwa Tribe.

Keeping with the spirit of designing this garden as a space of healing, Roos and the Burt Lake Band incorporated the Medicine Wheel as a physical representation of the garden’s layout. The Medicine Wheel also is apparent in the Burt Lake Band’s flag, whose colors coincide with the wheel. Anishinaabe traditions and Native American traditions as a whole tend to include beading patterns that would be incorporated as decoration on a variety of objects, “including (but not limited to) clothing, bags, birchbark baskets, jewelry, and traditional ceremonial wear… Motifs are often organized on materials symmetrically, featuring stylized flowers, leaves, or vines” (Roos, p. 20).

“The strongest designs have a deep underlying concept that defines each decision,” said Roos. “When I asked the Burt Lake Band what they hoped to happen at this site, they mentioned tribal council meetings, group gatherings and ceremonies, growing healing plants, and overnight camping. Many also mentioned the former executive director, Isabel Scollon’s, vision of the 3062 Indian Road property being a ‘place for healing,’ which then became the foundational concept for the entire project. This landscape design has been a collaboration every step of the way. The final design we developed intends to add layers of aesthetics, not just for aesthetics sake, but with the intention that the design would be entirely infused with cultural meaning. In this way, the garden and the landscape as a whole is an ever-changing cultural learning tool, as well as a restorative place to come together.”

Cultural Traditions into Physical Practice

This integration of cultural meaning can be seen through Roos’ integration of the 3D Medicine Wheel into the garden layout, as well as viewing each plant species as a bead that is a part of a larger design pattern.

“My advisor, David Mitchner, was so crucial in helping me understand the many ways this native plant palette could be arranged to further celebrate Anishinaabe aesthetics and traditional practices,” said Roos. “In the final design graphic, each plant is laid out like an individual bead in a curvilinear emotive beading pattern. When designing, I thought of each species of plant as a different color bead specifically sized to its mature width. The final bead-inspired planting design connects the arrangement of plants to these familiar curved, bright, and floral forms so often celebrated in Anishinaabe beadwork.”

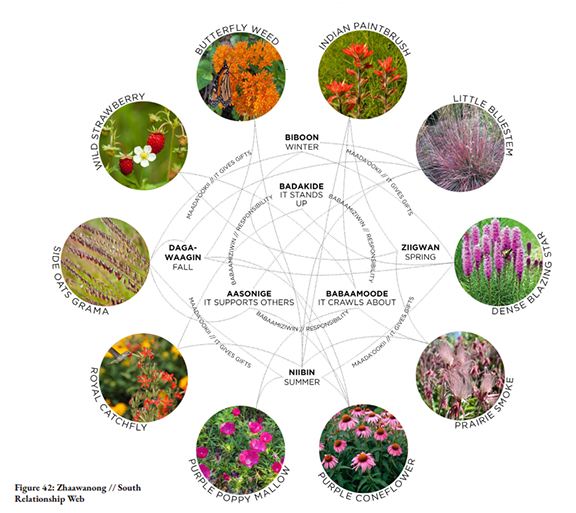

Roos added, "This landscape design is a practice in both translation and decolonization. To communicate knowledge about plants chosen for this garden, I produced graphics where ecological characteristics of plants are visualized through relationship webs—infusing animacy and an Anishinaabe way of knowing into this design.” An example of one of these relationship webs is shown in Figure 42. “Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Three Fires Confederacy, is frequently turned to as a teacher to better understand how plants, people, and culture relate to this landscape. Through a close examination of Cheboiganing Burt Lake Band history, their Elders, culture, language, and desires for their headquarters, a landscape design which supports healing—in all capacities— results.” (Roos, p. ii).

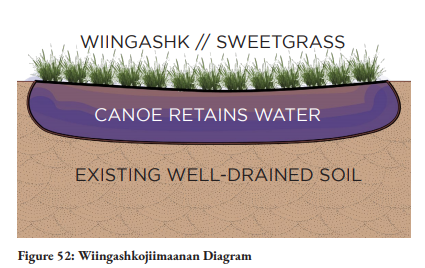

The Burt Lake Band also expressed a desire for Wiingashk, a sacred plant in their culture (known in English as Sweetgrass), to be a part of Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan. Roos explained, “This garden needed to be a low-maintenance garden, so every element of design was intended to reduce maintenance, though a garden by nature requires human care and interaction. An indigenized planting design needed to link planting choices to the site itself through the existing conditions of its soil, light, and the native range of the plants themselves. At 3062 Indian Road, the sandy soil drains very quickly and changes which kinds of native plants make sense here. Sweetgrass is native to Michigan, but not this particular site, because it requires a lot of water in the soil. Originally it was not included in the garden plan for that reason, but tribal members emphasized how culturally significant Wiingashk was to them."

She continued, "A strategy that my advisor, David Michener, knew of involved sinking vessels in the ground that will trap the water and create a wetter microclimate in the contained soil. I didn’t want to sink plastic vessels into the ground, and so the idea of burying canoes arrived since it is an important instrument for water transport in Anishinaabeg culture. The Wiingashk has been planted for two months now and is growing well. The plant has horizontal roots and planting it in a vessel with edges means you will be able to see the shape of the canoe as the Sweetgrass continues to grow. And this concept of Wingaashkojimaanin is a great example of the collective nature of the final landscape design; it resulted thanks to community input and knowledge of sacred plants combined with the guidance of teachers to help me creatively problem-solve. And as a result of all this collaboration, the project is coming to fruition!”

She continued, "A strategy that my advisor, David Michener, knew of involved sinking vessels in the ground that will trap the water and create a wetter microclimate in the contained soil. I didn’t want to sink plastic vessels into the ground, and so the idea of burying canoes arrived since it is an important instrument for water transport in Anishinaabeg culture. The Wiingashk has been planted for two months now and is growing well. The plant has horizontal roots and planting it in a vessel with edges means you will be able to see the shape of the canoe as the Sweetgrass continues to grow. And this concept of Wingaashkojimaanin is a great example of the collective nature of the final landscape design; it resulted thanks to community input and knowledge of sacred plants combined with the guidance of teachers to help me creatively problem-solve. And as a result of all this collaboration, the project is coming to fruition!”

Roos decided not to elaborate upon the traditions and uses of the plants themselves within her report in an effort to prevent the exploitation of any traditions held by the Band. “There is a real thirst within the tribe to reconnect to their roots and speak their traditional language, which was banned by law and erased from many within the boarding school system. I wanted to make sure I’m not giving information that is not mine to give. I’m not at all an expert in Anishinaabeg use of plants or ethnobotany, and I am not trying to extract that knowledge from this community. This is sacred knowledge that is reserved for those within the tribe. I hope that the resulting landscape and garden will become a resource for tribal members to learn more about these plants and their traditional uses, and they can share that knowledge on their own terms.”

Implementation and Future Goals for the Garden

The planting of the garden itself is a collective effort of Burt Lake Band tribal members as well as friends, neighbors, Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe members, and UMBS students, researchers, staff, and professors. Plants for the project were donated by the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Wildtype Native Plant Nursery, and the Feral Flora Native Plant Nursery.

There were numerous planting events at the site during Spring and Summer 2021, and the project is still ongoing. The garden is in need of more funding for signs that will detail the care and intention that has gone into the creation of the garden, as well as Anishinaabemowin and English signs detailing different cultural aspects of the site. If you are interested in helping the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians complete their project, please visit their Fundly page.

Roos said she is inspired by the work that took place as a result of community turnout and enthusiasm for planting Izhi-Minoging Mashkikiwan. “This project has been a great example of how social justice and indigeneity cannot be separated from landscape design—especially when it comes to native plants and ecology,” she said. Her work with the Burt Lake Band has led to another job working with the Grand Traverse Bay Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians on their Eyaawing Museum & Cultural Center, with the goal of creating “an ecological space that better reflects their indigenous identity and its intention as an exhibition space.”

“This project has been so rewarding,” Roos said. “The opportunity to entwine social justice and cultural traditions with landscape design is the type of work I would love to keep doing. Getting to know the people from the Burt Lake Band has been the most memorable and meaningful part of this collaboration. I was blown away that they were trusting enough to work with me, a complete stranger. They welcomed me so warmly into this community every step of the way. It continues to be an honor to collaborate and see the enthusiastic turnout of tribal members at these planting days, tucking plants into their forever homes. This garden is becoming their own, and they continue to show up and to make it happen. I can’t describe in words how rewarding it is to see this community view this project and landscape as theirs.”