back to all news

back to all news

Michigan pipeline standoff could affect water protection and Indigenous rights across the US

This article originally appeared in The Conversation and is reposted with permission.

Should states and Indigenous nations be able to influence energy projects they view as harmful or contrary to their laws and values? This question lies at the center of a heated debate over Enbridge Energy’s Line 5 pipeline, which carries oil and natural gas across Wisconsin and Michigan.

Courts, regulatory agencies and political leaders are deciding whether Enbridge should be allowed to keep its pipeline in place for another 99 years, with upgrades. The state of Michigan and the Bad River Tribe in Wisconsin want to close the pipeline down immediately.

My expertise is in Great Lakes water and energy policy, environmental protection and sustainability leadership. I have analyzed and taught these issues as a sustainability scholar, and I have worked on them as the National Wildlife Federation’s Great Lakes regional executive director from 2015 until early 2023.

In my view, the future of Line 5 has become a defining issue for the future of the Great Lakes region. It also could set an important precedent for reconciling energy choices with state regulatory authority and Native American rights.

A Canadian pipeline through the US Midwest

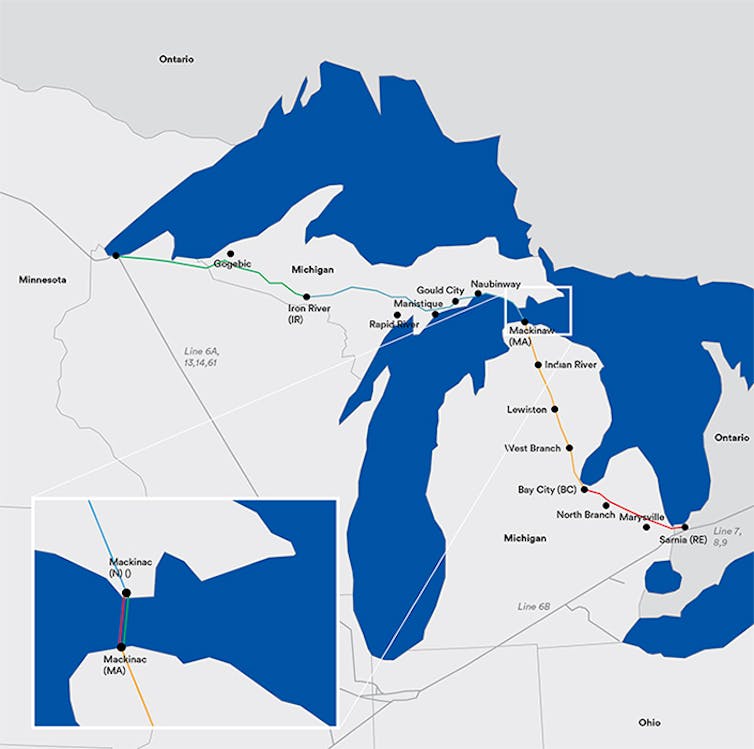

Line 5, built in 1953, runs 643 miles from Superior, Wisconsin, to Sarnia, Ontario. It carries up to 23 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids daily, produced mainly from Canadian tar sands in Alberta.

Most of this oil and gas goes to refineries in Ontario and Quebec. Some remains in the U.S. for propane production or processing at refineries in Michigan and Ohio.

Controversy over Line 5 centers mainly on two locations: the Bad River Band Reservation in Wisconsin, where the pipeline crosses tribal land, and the Straits of Mackinac (pronounced “Mackinaw”) in Michigan. This channel between Michigan’s upper and lower peninsulas connects Lake Michigan and Lake Huron.

Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline from Superior, Wisconsin, to Sarnia, Ontario, is part of a larger regional pipeline network. Enbridge, CC BY-ND

Line 5 crosses through the open water of the straits in twin pipelines that rest on the lake bottom in some stretches and are suspended above it in others. The route lies within an easement granted by the state of Michigan in 1953.

The Straits of Mackinac are one of the most iconic settings in the Great Lakes. They include hundreds of islands and miles of shorelines rimmed with forests and wetlands. Scenic Mackinac Island in Lake Huron, a popular resort area since the mid-1800s, is Michigan’s top tourist destination.

The straits also have long been spiritually important for Great Lakes tribes. Michigan acknowledges that the Chippewa and Ottawa peoples hold treaty-protected fishing rights that center on the Mackinac region.

The Line 6b spill

In 2010, another Enbridge pipeline, Line 6b, ruptured near the Kalamazoo River in southern Michigan, spilling over 1 million gallons of heavy crude. Line 6b is part of a parallel route to Line 5, and the cleanup continues more than a decade later.

The spill, and Enbridge’s slow, bungled response and lack of transparency, led to scrutiny of other Enbridge pipelines, including Line 5.

In a 2014 analysis, University of Michigan oceanographer David J. Schwab concluded that the Straits of Mackinac were the “worst possible place” for a Great Lakes oil spill because of high-speed currents that were unpredictable and reversed frequently. Within 20 days of a spill, Schwab estimated, oil could be carried up to 50 miles (80 kilometers) from the site into Lakes Michigan and Huron, fouling drinking water intakes, beaches and other critical areas.

This and other research intensified a burgeoning advocacy campaign by pipeline opponents, including regional and national environmental organizations, Indigenous leaders and advocates, and a newly formed network of local and regional businesses.

Pipeline supporters include the American Petroleum Institute and others in the fossil fuel industry, many conservative lawmakers, several key labor unions and the government of Canada. They argue that the current pipeline is safe, violates no federal laws and is a key piece of infrastructure that helps keep energy costs low.

Michigan revokes its easement

After years of scrutiny, including the formation of the Michigan Pipeline Safety Advisory Board and two expert reports commissioned by the state, analyses showed that Enbridge was violating provisions of its easement. Most notably, the section of Line 5 that ran under the straits lacked proper anchors and coating, increasing the threat of a rupture. The state concluded that the easement violated the public trust doctrine – the idea that government should protect certain natural resources, including waterways, for public use.

State reports concluded that the highest risk for rupture was from anchor strikes. Environmental nongovernment organizations found that Line 5 had already leaked more than 1 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids. On April 1, 2018, a boat anchor struck the pipeline and nearly ruptured it, temporarily shutting it down.

In 2019, Gov. Rick Snyder was succeeded by Gretchen Whitmer, who pledged in her campaign to close Line 5. Seeking to avert a shutdown, Enbridge proposed building a tunnel beneath the lake bed to protect the pipeline.

But after more analysis and another anchor strike that temporarily shut down the pipeline again, Whitmer issued an order in November 2020 revoking Enbridge’s easement and giving the company six months to close Line 5. The state sought a court order to support its decision.

Challenging state and tribal authority

Instead of accepting state orders, Enbridge resisted. The company argued that Michigan lacked authority to tell it how to manage the pipeline; that the project had not required an easement in 1953; and that building the tunnel would mitigate any risks.

Enbridge sued Michigan in federal court, arguing that pipeline safety regulation was a federal issue and that the state had no authority to intervene in what was essentially international commerce.

Enbridge also faced pressure from the Bad River Tribe in Wisconsin, where some 12 miles of the pipeline runs through the Bad River Band reservation and across the Bad River. Enbridge’s easement on parts of the reservation expired in 2013, and in 2017 the tribal council voted to evict Enbridge from their land, calling the pipeline a threat to the river and their culture.

When Enbridge continued operating Line 5, the tribe sued the company in federal court in 2019, charging it with trespass, unjust enrichment and other offenses, and sought to get the pipeline closed.

Today, Michigan’s case against Enbridge is bogged down in jurisdictional battles. But on June 16, 2023, the federal judge overseeing the Bad River case ruled largely in favor of the tribe and ordered Enbridge to stop operating the pipeline on tribal land within three years. Enbridge vowed to appeal the ruling, but is also seeking permits for a 41-mile reroute of Line 5 around the reservation.

Canada’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau, shown welcoming U.S. President Joe Biden to Ottawa on March 24, 2023, strongly supports Line 5, which carries Canadian oil and gas. AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

A national precedent

Line 5 is more than a Midwest issue. It has become a focus for national activism and is a major diplomatic issue between Canada and the U.S. President Joe Biden, who has worked to balance his ties with organized labor and his support for a clean energy transition, has avoided taking a side to date.

To continue operating Line 5, Enbridge will have to convince the courts that its interests and legal arguments outweigh those of an Indigenous nation and the state of Michigan. Never before has an active fossil fuel pipeline been closed due to potential environmental and cultural damage.

The outcome could set a precedent for other pipeline and fossil fuel infrastructure battles, from the mid-Atlantic to the Pacific Coast. Ultimately, in my view, Line 5 is an under-the-radar but critical proxy battle for how, when and under what authority the phasing out of fossil fuels will proceed.

Mike Shriberg is a professor of practice and engagement at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability.