back to all news

back to all news

Redlining and Environmental Racism

Homeownership has been a core value and aspiration for many American households over the last half century. However, beneath this ideal, there is a legacy of racist housing policies that left low-income individuals and people of color disproportionately exposed to the impacts of environmental burdens. These inequities can be traced back to the Great Depression when the U.S. was faced with a national housing shortage. During that time, the New Deal created projects to help stabilize the economy. Part of this process included segregating marginalized communities into urban housing projects so that White families could move into new suburban developments.

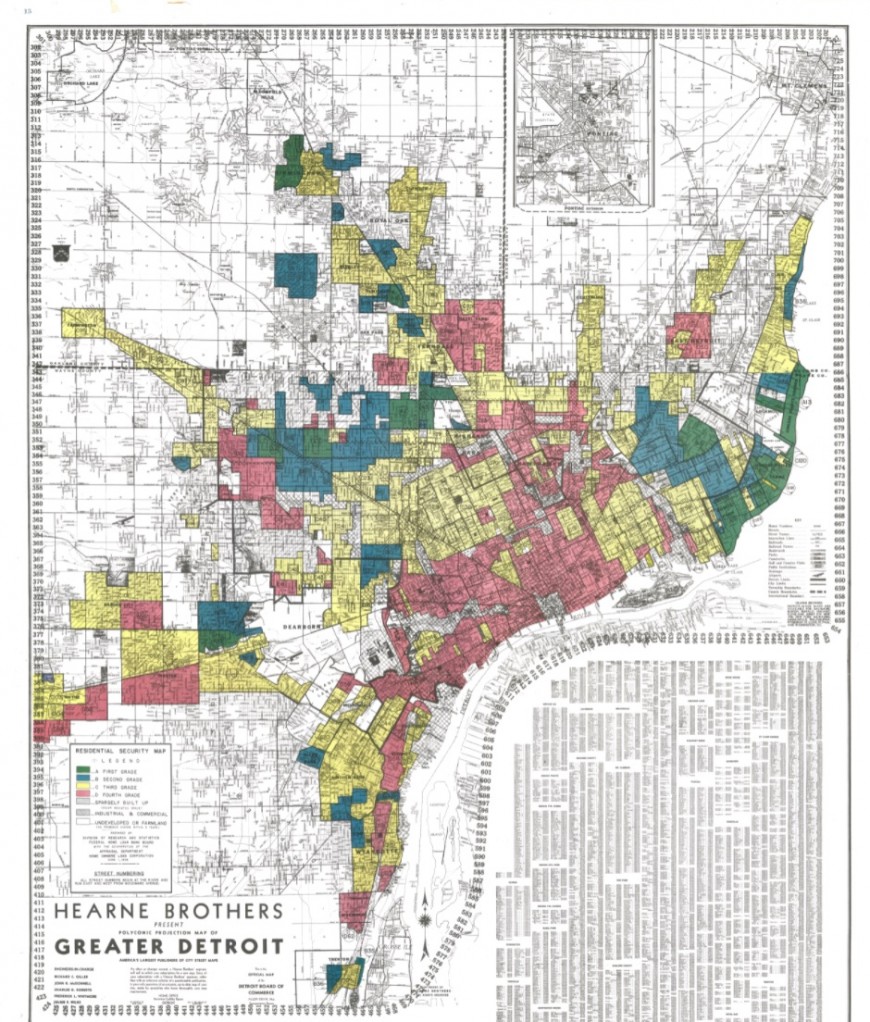

Segregation of housing stock became known as “redlining” and continues to reinforce unjust living conditions for minority residents nationwide. Understanding the history of housing policies illustrates why many cities still discriminate. In the 1930s, the federal government created maps that color-coded metropolitan areas based on the “safest” locations to insure mortgages. Minority neighborhoods were marked by the color red to indicate they were risky for investment based on racial biases. This practice resulted in privileged White families being favored for housing opportunities at the expense of minority homeowners who were denied loans.

Capital deprivation from marginalized communities contributes to a significant wealth gap between redlined and non-redlined regions. While affluence became concentrated in predominantly White areas, racialized ones were overlooked. Neighborhoods marked as high-risk for investment over eight decades ago are 74% low-to-moderate income and 64% minority today. The historical lack of resources, investment, and development resulted in poor infrastructure that increases vulnerability to environmental hazards, such as the urban heat island effect.

Redlining preyed on marginalized communities for new manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and highways—all of which are impervious surfaces that absorb heat. A study on 108 U.S. urban places showed that land surface temperatures are about 36 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in past redlined neighborhoods. The dangerous heat levels we see today can be linked to a combination of heat-trapping infrastructure, inadequate government investment in canopy cover, and minimal access to green spaces that cool down the city.

Exposure to extreme heat and other climate hazards have negative effects on human health. For example, prolonged high temperatures can lead to heart and lung complications that may be deadly or severely impact quality of life. Research has shown that these challenges are felt stronger in formerly redlined locations where heat is exacerbated and there is often less access to air conditioning and healthcare. People living in neighborhoods shaped by redlining can have shorter lifespans up to 30 years less than other nearby areas in the same city.

We can see evidence of inequitable hazards distribution in Michigan. One student team at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) created a map of environmental injustice hotspots throughout the state. The study revealed census tracts in Detroit, Grand Rapids, Flint, Saginaw, Lansing, and Kalamazoo as key places of concern. Such regions have the largest concentrations of minority and low-income residents vulnerable to burdens. According to the study, people in hotspots are more likely to encounter health risks like cancer from living near hazardous waste facilities, heavily trafficked highways, and Superfund sites.

It is no coincidence that census tracts identified in the SEAS project overlap with previously redlined areas in Michigan—these are environmental injustices. Findings from the student-team’s research recommend development of similar screening tools to help other states pinpoint neighborhoods strongly affected by environmental burdens. They say these tools can be used to advocate for policy that supports communities most impacted and protects them from hazards.

Policy creation should prioritize the voices of marginalized residents and frontline communities who were left out of decisions in the past. Coping with environmental challenges moving forward will require an understanding that not everyone is privileged with the same capacity to adapt. Our ability to sustain a just and safe world is dependent upon how we can avoid the mistakes of the past. Recognizing racist roots, calling out environmental injustices, and ensuring marginalized voices are heard is one small step towards a better future.

Consider exploring the history of your own city using a digital humanities tool. Mapping Inequality is an interactive site that houses records of redlining practices dating back to the 1930s. You can use this tool for exploring records and maps that show the footprint of redlining on racial inequities throughout the nation today.