back to all news

back to all news

SEAS Students Create Children’s Books about Environmental Issues

School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) Associate Research Scientist Sara Adlerstein-Gonzalez, an applied ecologist and visual artist, explores connections between art and science in her course Nature, Culture, and Landscape (EAS 501.119/ENV464.001).

“Some instructors teach courses because they have to. I teach this course because I love it,” said Adlerstein-Gonzalez. “My goal through this course is to bring inspiration and hope and improve the student’s perspective in relation to societal environmental change. This can be incredibly challenging within the environmental field because of the scale and severity of stressors such as climate change, but this hopeful perspective keeps me going in my scientific research and inspires me. It is also what I want to demonstrate for the students.”

The environmental humanities course, which has been taught by Adlerstein-Gonzalez since 2017, involves a core assignment: Pairs of students write and illustrate a children’s book that is used for environmental education. Most books are published through Michigan Publishing and are freely available through the SEAS electronic library. They can also be printed on demand.

Students are in charge of the entire creative process; they choose a topic within a theme—such as the Great Lakes or the Huron River—write a narrative, create visuals, and collaborate to develop their stories. The books serve as a conduit for children to learn about environmental issues and for students to “navigate the spaces between art and science,” said Adlerstein-Gonzalez. “Science in a bubble is not publicly impactful.”

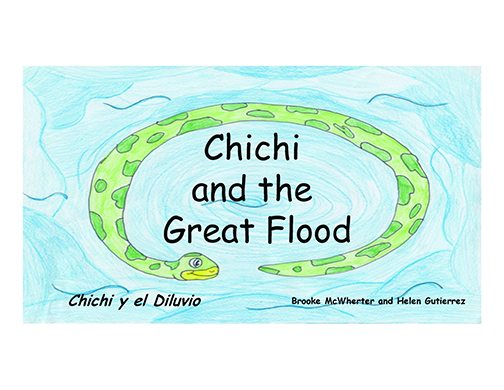

Chichi and the Great Flood, written in 2017 by Brooke McWherter (MS '18) and Helen Gutierrez (MS '18), has been used in a children’s environmental curriculum and is written in both English and Spanish for expanded impact.

“Sara’s class opened my eyes to a whole new world of possibilities, in terms of how we think about the world, our place in it, and our relationship with ourselves and others (whether human or non-human),” said Gutierrez. “Sara’s work in general inspired me to see that our work as environmental scientists/researchers/activists doesn’t have to fit the mold of the 'norm,' but that culture and art is also a valid way of expressing or communicating our findings, emotions, and perspectives."

She added: “My current work is focused on the impacts of climate change through a justice/critical lens, and in this space, culture plays a critically important role, precisely because the way that we move through the world is informed by the culture that we live in. If we truly want to effect change, culture has to be a part of the conversation. To that end, I’m currently leading a project where we created a space for people to come together to embroider and, at the same time, navigate what climate change is, how it affects us, and what climate justice looks like for us. Sara’s class was in large part an inspiration for this project.”

The story of Chichi the snake addresses climate change, pollution, and deforestation in a format that children can comprehend. ”Chichi and the great flood was inspired by multiple interests of ours,” said McWherter. “We both worked a lot in Latin America; I had served in the Peace Corps in Paraguay prior to SEAS and Helen is Costa Rican. Water and water conservation was an important factor in both of our work and experiences. We chose Chichi because it reminded us separately of stories that we had heard about guardian snakes. For myself, Paraguay has a myth of a snake with a parrot head called the Mbói Tu'I, which was considered a protector of aquatic animals and wetlands.

“I think our story demonstrates the importance of viewing environmental degradation and those involved as not done by any villain or with malice," she added, "but as activities engaged in by everyday people just trying to improve their lives, and that children and youth can play a role in modifying traditional methods and integrating sustainable practices with local cultures and needs in mind.”

The class also has been used to express environmental concepts through Indigenous traditional stories, such as in Mizhibizhu and the Black Snake, written by master's student Esha Biswas and John Petoskey (MS/JD '20) in 2020. The story centers on Mizhibizhu, a “creature revered by the Anishinaabe” who is a protector of the Great Lakes, and her fight against the Black Snake. Biswas and Petoskey chose to use the Black Snake to represent the Enbridge Line 5 Project and the risk it poses to the Great Lakes. Line 5, originally commissioned in 1953, moves oil from Canada to the United States and runs under the environmentally sensitive Straits of Mackinac. Enbridge is seeking to replace the aging system and is in legal conflict with the state of Michigan, which has requested that the section under the Straits be decommissioned.

Through the narrative of this children’s book, Biswas and Petoskey turn a politically fraught issue into an approachable narrative by expanding on a story from Petoskey’s cultural background. “We saw this project as a chance to uplift and amplify Indigenous knowledge and storytelling,” said Biswas. “Indigenous voices are essential to environmental healing and justice work, and I was excited to collaborate with Johnny on a story that incorporated a powerful figure like Mizhibizhu in a way that is accessible to children. The metaphor of the Black Snake is not our own; it has been used by various Indigenous water and land protectors as a metaphor for oil pipelines, notably in the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline. I have had the chance to share our book informally with children, and have loved using the story as a way of sharing Anishinaabe culture and issues with youth. Indigenous stories are often not given enough space in schools, and children's books can be a powerful way to introduce these stories to kids.”

Illustrations for Mizhibizhu and the Black Snake were created by combining photography, Photoshop images, and watercolor paintings. Photos of the Great Lakes taken by Petoskey were overlaid with Biswas' watercolor drawings, along with line drawings of various native plants that both had completed.

Eleven children’s books have been published thus far. Five more were created by last year’s class and will be submitted for publication soon. All of the books can be accessed online and printed on demand here. “The best scientists are creative,” said Adlerstein-Gonzalez. “Understanding science and how to utilize art and accessibility to promote sustainable changes to our society is vital for the future. This course is centered around students realizing and physically utilizing that power.”