To achieve the Michigan Healthy Climate Plan's goals to acquire 60% of the state's electricity fuel mix from renewable sources by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, the pace of utility-scale renewable energy development across the state must increase. Currently, deployment of renewable energy is slowed in part because local governments have not set standards for this infrastructure in their zoning ordinances. Without ordinances that represent local perspectives, projects can be slowed or terminated in localities when development plans do not align with the township’s priorities.

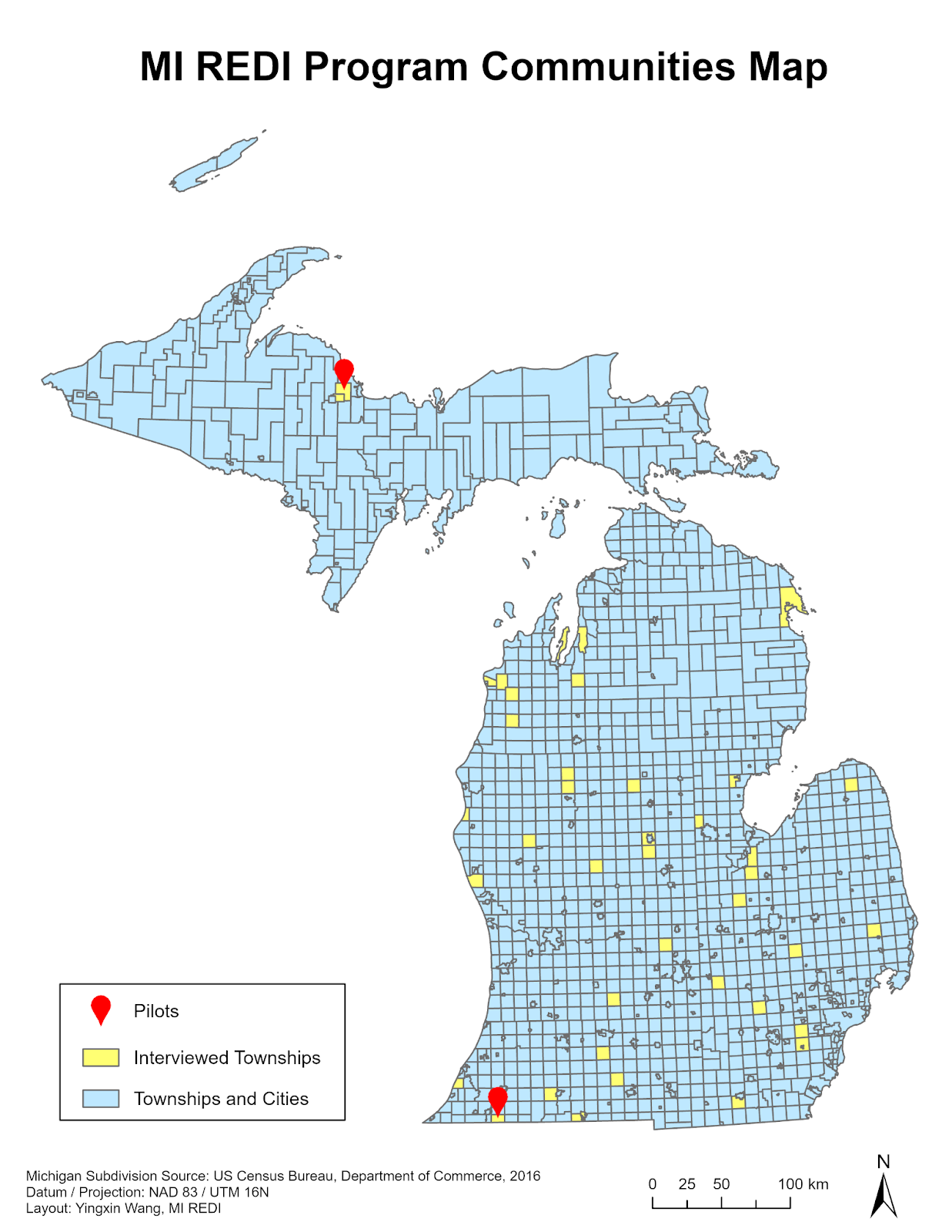

This project aimed to develop a program that streamlines renewable energy siting by providing townships with recommendations and resources needed to write zoning ordinances that reflect community perspectives. To inform the program strategy, interviews were conducted with local government officials in 24 Michigan townships to gauge current barriers to proactive zoning and identify strategies to facilitate zoning processes. The team then collaborated with two townships to pilot the program, which culminated in the delivery of customized recommended ordinances for utility-scale wind and solar for each township. In this report we provide recommendations to our client, Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), for future iterations and rollout of the program. While key takeaways from this process emphasize the importance of collecting more robust community opinion data to ensure zoning decisions fully capture local preferences and further piloting is necessary to optimize programming, the Michigan Renewable Energy Development Initiative (MI REDI) model enhanced community discussions and understanding of the potential role of utility-scale renewables in local landscapes.

Ian O’Leary, MS (Sustainable Systems)

Kaitlyn Sledge, MS (Sustainability and Development)

Sarah Dieck, MS/MPP (Behavior, Education, and Communication)

Sophie Farr, MS (Environmental Policy and Planning)

Yingxin Wang, MS (Geospatial Data Sciences)

Zona Martin, MS (Environmental Policy and Planning)

M.S. in Environmental Policy and Planning from the School for Environment and Sustainability

M.S. in Sustainable Systems at the School for Environment and Sustainability

M.S. Candidate in Behavior, Education, and Communication at the School for Environment and Sustainability, and MPP Candidate at the Ford School of Public Policy

M.S. in Geospatial Data Sciences at the School for Environment and Sustainability

M.S. in Environmental Policy and Planning at the School for Environment and Sustainability

M.S. in Sustainability and Development at the School for Environment and Sustainability

To achieve the Michigan Healthy Climate Plan's goals to acquire 60% of the state's electricity fuel mix from renewable sources by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, the pace of utility-scale renewable energy development across the state must increase. Currently, deployment of renewable energy is slowed in part because local governments have not set standards for this infrastructure in their zoning ordinances. Without ordinances that represent local perspectives, projects can be slowed or terminated in localities when development plans do not align with the township’s priorities.

Michigan Renewable Energy Development Initiative (MI REDI) is designed to support townships seeking to proactively zone for renewable energy development through a three pronged approach.

Before program design could begin, the MI REDI team needed to hear from local government officials and renewable energy developers about their perspectives on current barriers to renewable energy zoning in Michigan. While these two viewpoints are different in some ways, we expected to also find commonalities and points of compromise that could be addressed by the MI REDI program.

Interview requests were sent via email to these township contacts. The outreach emails included a brief description of the objectives of the MI REDI program, purpose of the interview process, and scheduling information. If a township did not respond to the email within two weeks, they received one follow-up email. If there was no response after two attempts to connect, they were not contacted again. A total of 50 emails received responses, and 24 township candidates agreed to and followed through with interviews.

Six representatives of utility companies and renewable development companies were reached out to, five of which provided interviews to MI REDI. These contacts were made without rigorous methodology; instead, we were advised to pursue certain connections and made others at conferences.

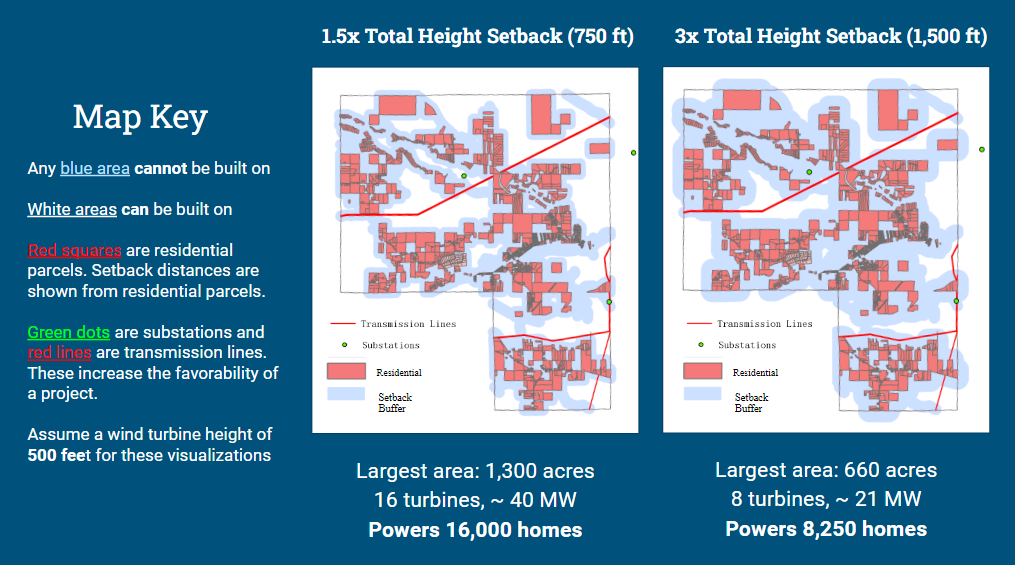

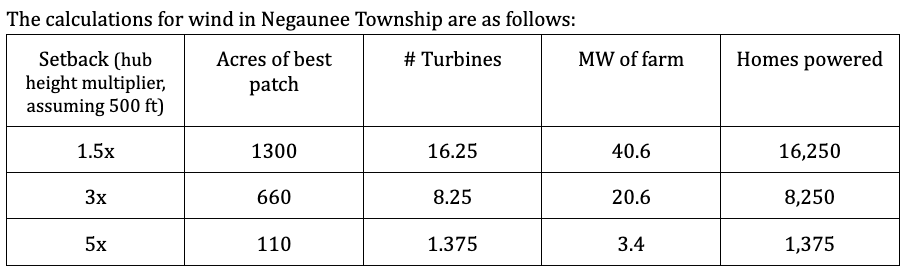

The MI REDI team used several pieces of software to perform a resource assessment, including the Energy Zones Mapping Tool (EZMT), ArcGIS Pro, and Excel. EZMT is an online mapping tool that displays resource potential for wind and solar, including multiple weighted factors such as wind speed or sunlight availability, land cover type, distance to substations and major roads, slope, population, whether the area is protected land, and more. A shapefile data of the township’s parcels was added on top of EZMT’s resource potential visualization to visually identify parcels that may be impacted by nearby renewable installations. Based on that, the team used the buffer function from ArcGIS Pro to display various setback distances originating from nearby residential parcels and roads. Maps with varying setback distances and example locations of available land for each were the final product. For wind, the visualized values were a property line setback of 1.5x, 3x, and 5x a 500 foot turbine; for solar, we applied a 150, 300, and 500 foot property line setback.

Then, for each setback, MI REDI selected a continuous, non-excluded “patch” of potentially developable land based on access to transmission lines and substations, and resource potential and measured its acreage. For solar, the acreages of available “patches” were extremely large. As such, to estimate how large an actual installation on that plot would be, a buffer of 150, 300, and 500 feet was applied to every property line within the selected patch to visualize a percentage of a patch's total acreage that would be available and excluded.

Based on these final acreage values, the team produced an estimate of how much wind or solar could go into the respective space and how many homes this could power. This process was repeated for each setback to clearly illustrate the reduction of hypothetical generation as setbacks increased. Resource potential was not involved in the calculation; it was simply used as a selection criterion for which “patch” to measure the acreage of. An example of the final output of the resource assessment phase appeared in Figure 8 below.

This visualization would not be asserting that a setback of a certain size would see a solar field installed on a certain parcel; instead, it would use a township’s unique parcels to support a statement like, “reducing the setback from X to Y could potentially yield a capacity increase from X to Y.” Additionally, if the trend was significant enough to report, we could show how certain areas within the township have more developable land (i.e. not excluded by the setback and high potential) than elsewhere, potentially highlighting certain zoning districts as particularly apt for renewables installations.

With how contentious utility-scale renewable energy projects can become when a developer enters a township that lacks a renewable energy zoning ordinance, the MI REDI team wanted to approach the community engagement process in a way that gives the community agency and that encourages collaboration between the program facilitators, the township residents, and eventually the township planning commission and elected board. Most importantly, the MI REDI team wanted to avoid giving the township residents the sense that a team of researchers or government-affiliated consultants were entering their community and telling them what they should or should not do. Instead, the team aimed to construct an adaptive engagement strategy that was tailored to the specific interests and needs of the community, and act as a resource to assist in the township’s conversations around renewables. While the township officials in the two pilot townships both decided on the same strategy, future pilots might request different engagement approaches, and MI REDI’s community engagement strategy should accommodate that. Further pilots are necessary in determining the best practice in navigating the complex roles and most effective strategies of the MI REDI program. The community engagement strategy was designed to be a continuous process throughout the pilot timeline, beginning in September with Postcard mailer 1, and ending with Town Hall 2 in December.

Postcard mailer 1: The first mailer introduced the partnership between the township and the MI REDI program and advertised the Town Hall 1 meeting. The printed mailer included a link and QR-code to a Google Forms survey on the back of the postcard inviting residents to express their opinions about utility-scale renewable energy and to pose any questions and concerns about these projects. The survey was communicated as being the mode to guide the topics of conversation at the first town hall meeting, further encouraging residents who filled out the survey to attend. The survey provided the team with a general sentiment surrounding public attitudes towards renewables as well as willingness to participate in conversations around how or if renewable energy projects might fit in the community. The survey was mutually beneficial, serving as a valuable introduction to the community residents, allowing the town hall meeting partners time to prepare answers posed by the residents, and providing an avenue for residents to individually state their opinions on the topic on an anonymous platform.

Town Hall 1: The first town hall meeting involved the township official and a Michigan State University (MSU) Extension staff member explaining the purpose of the partnership between MI REDI and the township and providing information through a PowerPoint presentation format to address the questions residents had asked in the survey about utility-scale renewable energy. Almost every concern raised in the survey was addressed in the presentation. The MI REDI team attended the town hall meeting through Zoom and was available to answer any questions the township official or the MSU Extension staff member directed to the team.

Postcard mailer 2: The second and last mailer advertised the last town hall meeting and communicated to the community that the purpose of the town hall was to gather community feedback on zoning considerations for utility-scale renewable energy. The second town hall was designed as a continuation of the first, but the second mailer invitation was extended to everyone in the township in the interest of having as much transparency and attendees as possible.

Town Hall 2: The second town hall involved providing each attendee with an interactive worksheet and presenting a slideshow presentation explaining the various zoning considerations for renewable energy developments. Throughout the presentation, attendees were encouraged to fill out on the worksheet their preferences for each zoning item. These worksheets were collected at the conclusion of the meeting to be coded by the MI REDI team into figures that can be used to inform zoning decisions made in the zoning assistance portion of the program, as well as by the township planning commissions during their own official zoning process. The presentation and worksheet were designed with considerable feedback from the township officials and MSU Extension staff on what they found to be most helpful in informing the recommended zoning ordinance. Because utility-scale renewable energy zoning can be a contentious topic, the final town hall highlighted some useful strategies for maintaining productive dialogue and de-escalating tensions when walking through zoning considerations. A successful strategy used by the town hall facilitators involved providing the clarification that legally, banning renewable energy was not an option. Rather, the township would be adopting a renewable energy ordinance and the residents could use the town halls as a method of collectively deciding the size, placement, and method of potential future development.

The ultimate goal of community engagement efforts was to gather local opinions on utility-scale renewables, which would then be incorporated into a draft zoning ordinance and handed off to each pilot township's respective planning commissions, who could then modify or keep as much of the material as they deemed useful. As mentioned previously, the MI REDI team utilized sample zoning templates for utility-scale renewables (one for wind, one for solar) from Michigan State University and Graham Sustainability Institute, which were then adapted into fillable zoning worksheets based on township officials' input. These worksheets were then presented at the final town hall meeting, whereby residents filled in their preferences on zoning items. The specific format of the worksheet questions varied from a binary 'yes' or 'no' option to a ranked choice, and for many questions participants were given the option to write in notes, concerns, or anything else they wanted to share. After these final meetings, the MI REDI team analyzed the worksheets, illustrating which items attendees felt most strongly should or should not be incorporated into a zoning ordinance. This was done by giving each option in a given question a weighted score based on how highly it ranked (for example, a first place ranking out of five options would grant that option five points, while a last place ranking would grant it one point). These points were then gathered from every worksheet to aggregate the township’s ranked preferences at large.

The preferences receiving the majority of votes for each zoning item were then incorporated into the MSU sample templates, which were handed off to township officials with detailed notes explaining further context where necessary. It is important to emphasize that throughout the community engagement process and during the final town hall meeting, residents were encouraged to zone either permissively or restrictively for utility-scale renewables - the ultimate goal of the process was to establish some sort of zoning to ensure that the township will be ideally positioned when approached by developers in the future.

This project would not have been possible without the enthusiastic support of our advisor Dr. Sarah Mills, and the trust of our clients at EGLE, Julie Staveland, Cory Connolly, and Zach Richardson. The time and expertise of the two Michigan State University Extension Educators who worked with us were invaluable to the facilitation of the four town halls; you both deserve more recognition than a cookie basket and our thanks. To every township official, developer, and planning professional who agreed to speak with us during the summer of 2022, your perspectives shaped our understanding of renewable energy in Michigan and informed many decisions throughout the development of this program. Lastly, to the friends and family of the MI REDI team who lent emotional support and stability, and to everyone who provided support, advice, editing, opinions, time, or otherwise assisted in seeing this project to completion, we thank you.