back to all news

back to all news

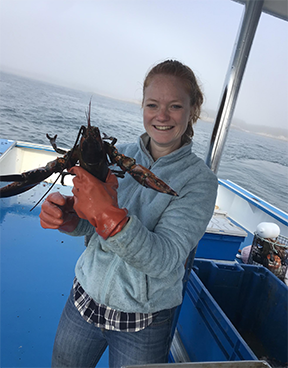

Navigating change: SEAS student explores fishermen’s views on aquaculture in Maine’s warming waters

Kate Shambaugh (MS ’25), who is originally from Portland, Maine, earned her Bachelor of Science in neuroscience and psychology at Smith College with a focus on human behavior. Initially aspiring to become a clinical pediatric psychologist, she dedicated her time to extensive research but began questioning this path as burnout set in. During her final semester, Shambaugh participated in a study abroad program in New Zealand, conducting oceanographic research, sparking the idea to combine her background in human behavior and climate change science.

This experience led her to explore environmental work through roles in youth and outdoor education and experience with the nonprofit Portland Parks Conservancy. However, Shambaugh wanted to dive deeper into the field of climate change science and its intersections with human behavior, leading her to pursue a Master of Science degree at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS), where she is specializing in Behavior, Education, and Communication.

Growing up on the coast of Maine, Shambaugh’s passion for its working waterfront and the communities whose living relies on it, has only grown stronger as she learned about the dramatic shifts in marine life caused by climate change. Therefore, her research focuses on lobster fishermen and their receptiveness to aquaculture, given that climate change is affecting their livelihood. Living along the coastline, she was well aware of the media’s portrayal of conflict between lobster fishermen and aquaculturists.

“The media often publishes bold headlines painting a narrative of lobster fishermen as completely opposed to any aquaculture. Conflict sells in the media, and its narrative says that all lobster fishermen are resistant to aquaculture,” Shambaugh explained. "The truth is that none were opposed, but many had concerns that they believed needed to be addressed. Many emphasized that as long as strong regulations were in place and local wildlife was monitored and unaffected, they didn't have an issue with aquaculture."

From SEAS Professor Raymond De Young’s classes, Shambaugh learned about the importance of involving the community at every step in grassroots work and community-based research. She believed the media’s narrative stemmed from a lack of communication between the fishermen, researchers and the media. This led Shambaugh to question, "What are lobster fishermen’s actual opinions of aquaculture, and are the media headlines true?”

Lobsters are Maine’s largest source of economic productivity and are highly vulnerable to climate change. As cold-water animals, they migrate to deeper and colder waters to escape rising sea temperatures. However, deeper and colder water lessens the time it takes for them to molt, making them more susceptible to diseases. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 97% of the world’s oceans, threatening not only lobster populations but also Maine’s economy and the communities that have relied on the fishing industry for generations.

Many ideas have been proposed to diversify Maine’s economy and provide alternative livelihoods for its fishermen. One promising avenue for Maine’s blue economy is aquaculture. According to researchers, the Gulf of Maine is ideal for breeding and harvesting seaweed and shellfish, Shambaugh noted. However, fishing is one of the oldest professions in the United States and is deeply rooted in Maine’s heritage. “Some fishermen told me their genealogy goes back at least eight generations,” said Shambaugh. “This shows that fishing is not only ingrained in Maine’s history but also in its traditions, emotions, and culture. Therefore, finding a way for Maine fishermen to stay on the water is really important.”

Eager to get to the bottom of this, she went straight to the source, returning to her home state to interview “some of the most famously stubborn individuals in the country: Maine lobster fishermen,” said Shambaugh. With a grant from the Sustainable Ocean Alliance and Environmental Defense Fund, she began her research in Washington, D.C., where she met with New England congresspeople about her project and concerns. “My trip to D.C. motivated me and got me excited about my work. While I was there I learned how important it is to meet staffers face to face as they have a lot of pull in what interests representatives have and what gets done.”

Shambaugh spent the entirety of May traveling Maine’s coastline, interviewing fishermen on their docks, in their homes, at local pubs and around the cribbage table. Speaking to folks on the ground has only made her more passionate, said Shambaugh. Reflecting on her interviews, she expected the most conflict in Downeast Maine. “It's a tiny town and one of the oldest fishing towns in the country. It’s also one of the poorest counties in the country. They eat, sleep, drink fish; they are at the heart of it, so I figured they wouldn’t change.” To her surprise, of the more than 76 fishermen she spoke to, not a single one was opposed to aquaculture if strong regulations are in place. This finding has given her a “sense of purpose because the general consensus of lobster fishermen’s opinion of aquaculture, I’m learning, is wrong,” emphasized Shambaugh.

Key Takeaways

Shambaugh underscored the importance of meeting the community where they’re at when doing community work. For years, the media misrepresented Maine lobster fishermen, creating an environment of distrust. At first, many of the lobster fishermen she approached assumed she was a reporter and were not open to having a conversation. Thus, she set out to get to know the Maine fishing community in the best way she knew how: cribbage. “I went down to the gas station where my Airbnb host told me everyone plays cribbage, grabbed a cup of tea and was like, ‘Oh nice, a cribbage board,’ and they asked me if I wanted to play,” Shambaugh explained. “The first day, I didn’t ask any questions, I just played cribbage. But what I learned is that if you can get someone to talk to you for 30 seconds, they’ll talk to you for hours. I had a lot of informal interviews this way because if you bring out a recorder, you’ll spook them.”

Shambaugh also learned how to approach polarizing topics in a way that didn’t shut down a conversation or steer the person away. Many of these communities are very conservative and don’t believe in climate change, said Shambaugh. “I never mentioned climate change directly, but I always asked if they noticed any changes in the waters and the harbors. This made it easy to segue into environmental topics, like asking how they made out in the storm last year,” she explained. “People would then mention changes they had observed, even if they didn’t attribute them to climate change. They might push back against climate change, but they’ll talk about how the lobsters are moving a lot.”

Once the trust was gained, Shambaugh noted how remarkable it was to converse with the fishermen from a scientific perspective while gaining insights from their on-the-ground experience. “It was really cool to be in these communities where we could just talk and build relationships over a mutual goal. I’ve had countless wonderful experiences that I wouldn’t have had without this project,” Shambaugh reflected.

Shambaugh said her biggest lesson was to just listen. Oftentimes, assumptions, language and biases can get in the way of decision-making, and “the loudest voices in the room aren’t the only ones,” said Shambaugh. While science and research are very important in terms of climate adaptation and mitigation, the folks who are directly impacted are the ones “who can actually make a difference,” Shambaugh concludes.

Barriers to the Aquaculture Industry

Shambaugh found that some Maine fishermen are eager to start their own aquaculture farms but face many barriers. During a hearing in Beales Island, Maine, about a restriction to limit the size of aquaculture farms to five acres, a fisherman passionately argued for expanding the size limit. “Five acres may be enough to make a small change, but it’s not enough to make a living off of,” Shambaugh said. The fisherman explained how aquaculture could help Maine fishermen build resilience, but every single policymaker at the hearing shut it down. “It was 21 to zero, with no discussion. They basically told him to come back with a better deal,” Shambaugh said.

When speaking with fishermen, she discovered that the main obstacle preventing them from pursuing aquaculture farming is the time it takes to get a lease. Aquaculture leases, which vary by specific type of marine farming (such as kelp, clams, or oysters), are categorized into three levels: experimental, standard, and limited-purpose (LPA). Each lease requires a local hearing by the town government for approval. LPA leases, designated for specific species that occupy no more than 400 feet, are typically reviewed within several weeks. Experimental leases are reserved for commercial or scientific research limited to four acres and are processed in six to 12 months. Meanwhile, standard leases are larger in size, allowing up to 100 acres for a duration of up to 20 years. Typically used for finfish, shellfish and marine algae, these leases can take anywhere from six months to three years to be processed. “The biggest hiccup I’ve heard from everyone is they’ve been trying to get a lease for years, and they’re still on the waiting list,” explained Shambaugh.

Next Steps

Shambaugh spent the rest of last summer in Southern Maine completing her interviews. She is working with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute to finalize a report that will synthesize her findings. She intends to send the report to legislators in Maine and New England policymakers with the aim of informing policy changes, especially when it comes to “expediting the process in starting an aquaculture lease, or at least put more attention on the process of starting a lease,” Shambaugh said. Additionally, she hopes this research ultimately supports the Maine fishing community in its transition to aquaculture and bolsters their climate resilience.

While Shambaugh remains uncertain about her future career path, her practicum has shown her how she wants to continue resilience-building work with specific attention to the coastline. “I am emotionally, if not physically, invested in the history of the fishing industry and the working waterfront of Maine,” Shambaugh emphasized. “Maybe it’s because I grew up on the water and love it, but I think it’s a great pathway to combine my background in human behavior and climate change. As I question what I want to do, I keep coming back to the coastline and Maine’s fishing community.”