Protecting the Diversity of Fish in the Great Lakes

SEAS Assistant Professor Karen Alofs has been co-teaching Biology & Ecology of Fishes to U-M undergraduate students for years. And the one thing she never tires of seeing is how excited students get when they hold a fish for the first time.

“Students are always amazed at the diversity of fish they’ll catch, even if they’ve been angling all their lives,” says Alofs. “Usually, they’re catching the same three to five species, but out here they’ll catch some beautiful fish, like the Johnny darter or the Iowa darter. It gives them a different perspective on biodiversity.”

A four-week summer course held at the U-M Biological Station, Biology & Ecology of Fishes gives students the hands-on opportunity to study fish in their natural habitats. The “classroom” includes Douglas Lake, Maple River, Carp Lake River and the nearest shore of Lake Michigan.

The nine students also head into Suttons Bay aboard a 77-foot schooner owned by the Inland Seas Educational Association, where they do offshore trawling.

“The focus of the course is for students to make observations about fish in their natural habitats so they might be able to understand something about the change in ecological or evolutionary time,” says Alofs, who co-teaches the course with Hernán López-Fernández, an associate professor in U-M’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Both professors also teach in U-M’s Program in the Environment.

“We teach students about why some fish species occur in certain places and not in others, and how environmental change might impact them,” Alofs adds. “We also teach them how to catch fish and collect specimens that are contributed to U-M’s Museum of Zoology for their long-term collection.”

Environmental Factors Affecting Fish

One environmental change that impacts freshwater fish is invasive species, notes Alofs, which students see first-hand in their fieldwork. Last summer in Suttons Bay, for instance, students caught hundreds of round gobies, which eat the eggs of other fish species, while in Douglas Lake, they saw plenty of zebra mussels.

“It’s impactful for students to see,” says Alofs. “The water here is a little bit less impacted by contaminants and development because we’re up north, but those are certainly things we’re thinking about as well.”

Alofs, who runs the Freshwater Conservation Ecology Lab at SEAS, studies how environmental stressors like climate change, invasive species and habitat degradation impact fish. One of the species she studies is walleye, a cool-water adaptive species that is important for recreational and commercial fishing—and to Native Americans—in the Great Lakes.

Walleye have been declining in population due to warming water and an increase in water clarity resulting from zebra mussels, says Alofs. Working with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, she is studying how genetics and water temperature might influence the success of fish when they’re stocked into lakes.

So far, more than 2,000 volunteers from around the world have helped to transcribe 100,000 historical records about lake conditions and fish differences.”

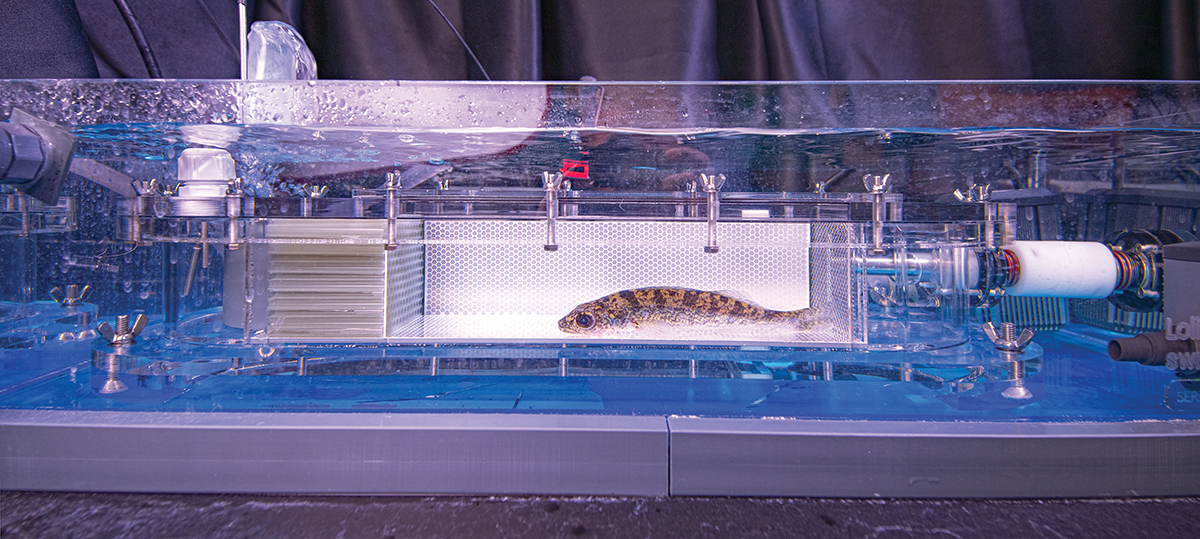

“We’ve been looking at their metabolic rate, which can be strongly influenced by temperature, and how it relates to how much food demand they have for their activities,” Alofs says. “As temperature increases, the metabolic rates change in ways that may mean walleye will have less energy for growth and reproduction and foraging.”

Another project Alofs is working on involves collaborating with the Institute for Fisheries Research to “crowdsource” the digitizing of historical lake data from the last 100 years. So far, more than 2,000 volunteers from around the world have helped to transcribe 100,000 historical records about lake conditions and fish differences.

Using the historical data, Alofs and her team will develop models to predict how climate change will impact fish growth and abundance in the future.

“We’re using this historical data to look at what changes have already happened with fish and see how models could have predicted those changes,” says Alofs. “We’re looking backward instead of forward to understand the impacts of climate change and other factors on these fish.”